_____

Marvelous Marvin Hagler vs. Thomas “The Hit Man” Hearns

Caesars Palace, Las Vegas, April 15, 1985

Announcers: Al Bernstein and Al Michaels

Alley War Poetry

The pugilists are in the desert, somewhere far from most of humanity and society. They are at a resort, however, a magnificent getaway, elevated in the middle of a roped-off ring, with cameras surrounding. They have taken the center of the world from us, and placed it into that squared area they occupy. They are poets, informing us of brutality and violence from this very different point of view.

We must relinquish our individual world centers to theirs, but in doing so, these centers merge in passing. In the merger, the metaphor is no longer a metaphor. It does not stand for affecting our lives; it affects our lives. Thus created is poetry, a poetry written before a word is spoken, before the words for it are thought of, and in vivo. Marvelous Marvin Hagler and Thomas Hearns are scripting the wordless narrative out of earshot, the good and the bad of it, a new violence for us upon first viewing, something to reflect upon afterward, something brutal with important aspects, both a metaphor and a reality to re-use for different purposes, even now again, 22 years later.

There is poetry to be found in violence. Poetry is not anti-war as such. Witnessing a four-dimensional Rubik’s cube with one color wrong, the alley war poet intuits how much unravelling must be done for a short period of resolution, until new aspects bear themselves into the world, and the cube must be re-solved–this whether one or a billion dark sides surface the wrong way, whether in times of peace or war. Violence will always be an unsolved part of the whole of us and each one of us. Indeed, when he was 13, Hagler’s home was destroyed, and people around him killed, in the race riots in Newark. But as an athlete poet, when his ideas and rhythms prevail, he is prevailing, and his message comes through.

There is poetry to be found in violence. Poetry is not anti-war as such. Witnessing a four-dimensional Rubik’s cube with one color wrong, the alley war poet intuits how much unravelling must be done for a short period of resolution, until new aspects bear themselves into the world, and the cube must be re-solved–this whether one or a billion dark sides surface the wrong way, whether in times of peace or war. Violence will always be an unsolved part of the whole of us and each one of us. Indeed, when he was 13, Hagler’s home was destroyed, and people around him killed, in the race riots in Newark. But as an athlete poet, when his ideas and rhythms prevail, he is prevailing, and his message comes through.

Civilly speaking, the fight could, and arguably should be stopped (if it should have taken place at all), upon Hagler’s profuse bloodshed. In earlier ages and other places, such an event would be a fight to the death, though. This violence and brutality of boxing matches are not in our civilized centers of commerce and community centers, but under the preserve of state sanction and institutional procedure. Even still, boxers like soldiers, our young adults die and become disabled through their fighting. We understand that such brutality exists, and make it against the law. Our society, through our humanity, has drawn legal and moral lines.

Civilly speaking, the fight could, and arguably should be stopped (if it should have taken place at all), upon Hagler’s profuse bloodshed. In earlier ages and other places, such an event would be a fight to the death, though. This violence and brutality of boxing matches are not in our civilized centers of commerce and community centers, but under the preserve of state sanction and institutional procedure. Even still, boxers like soldiers, our young adults die and become disabled through their fighting. We understand that such brutality exists, and make it against the law. Our society, through our humanity, has drawn legal and moral lines.

Yet, we are able, through such an event, to allow our shadows, what is inhumane of our humanness, to be spoken to. This is an aspect of life that has never gone away. Like the sex drive, it may either be brought out orgiastically; or in recession, monastically; but it remains part of us. The taller we are in the light, the longer the shadow, from each given vantage point. Hagler, for instance, his entire adult life, no matter where he has lived, has given himself to causes for children, as they mature in the world, and as they die in hospitals.

Sometimes the line before violence and brutality disappears. This can happen within the individual, within families, within social groups or gangs, and, during wartime. Poetry may unveil this.

by Wilfred Owen

Dulce Et Decorum Est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys!–An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime . . .

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Wilfred Owen gives us brutal word poetry here, the violence everpresent in being human is heavy, the darkness brought to light. From where he stood, the darkness is out in the open. The events in this poem, however, were neither staged nor so scripted by the people doing the violence. The main character, the hero, is dying, then dead. It is gruesome. The poem existed where muses exist, and was written into words by one who would otherwise be a background player, one of the other soldiers.

But where is the poetry? Is it in his words? Not essentially. Essentially, it is in the unfolding story. It is pre-verbal: Chopin, Marceau, and Hagler. In this sense what we usually think of as poetry, is a sub genre. It is word poetry.

Let’s attempt to shift the metaphor of the poet from the pugilists to the announcers, Bernstein and Michaels. This makes Hagler and Hearns the main characters in an unfolding drama. The announcers are witnessing an event. Before their eyes, two warriors with great heart, hope and humanity are duking it out. A golden story seems to be unfolding, inspiring them. Bernstein and Michaels are streaming their words, as they relate this to us, their imagined audience, spontaneously, with repetition, simile, metaphor, alliteration, and meter that together borders on the music of song. Sometimes they really are singing.

This, then, could be thought of as a (p)entacostal event. The shaman (here, the pugilist) takes the journey into the breadths and depths of human nature, and comes back with something that the village priest is capable of interpreting into the lives of us lay people. Nowadays, the poet is expected to do both, take the inspirational journey of the hero, and then write it down for the rest of us to read and re-center from, or at least keep in our pockets for later reference. But there is a catch.

When Owen wrote Dulce Et Decorum Est, it was reflective. His journey was internal and after-the-fact. A poet may tell us fiction, but Owen relates something that had happened, something he witnessed in real life. Both the essential poetry and the verbal poetry came from him–what we have come to expect from our poets. Note too that, although it is often recited, the poem’s birth event is in written, not spoken, form–not to say he was not whispering or even singing the lines as he composed, maybe he was. Nor was he dancing or beating a drum. Both Hagler and Hearns, however, were in their ways dancing. Our shamans speak to us in many ways.

Bernstein and Michaels have a poetic event unfolding before them. Their poetics are of the spoken language kind (and here I don’t mean to compare or even debate poetic ability, simply to grant that they speak in verse). Note instead, that their rhythms are different from the rhythms of the fighters. That’s the catch I mentioned. It is a split we witness, between the movement and focus of the pugilists, and the versification of the announcers. The event a poet relates, is decidedly different from the event of its relating. The verbal poem has a different sense, sound, and rhythm than the essential poetry inspiring it.

In case there is any tension, let’s bridge this gap between the spontaneous relating of an inspirational event, and the practiced writing of poetic reflection. Here is Jack Kerouac’s spontaneous bop prose, as he called it, in “On the Road”:

“He’s mad,” I said, “and yes, he’s my brother.” I saw Dean coming back with the farmer in his tractor. They hooked chains on and the farmer hauled us out of the ditch. The car was muddy brown, a whole fender was crushed. The farmer charged us five dollars. His daughters watched in the rain. The prettiest, shyest one hid far back in the field to watch and she had good reason because she was absolutely and finally the most beautiful girl Dean and I ever saw in all our lives. She was about sixteen, and had Plains complexion like wild roses, and the bluest eyes, the most lovely hair, and the modesty and quickness of a wild antelope. At every look from us she flinched. She stood there with the immense winds that blew clear down from Saskatchewan knocking her hair about her lovely head like shrouds, living curls of them. She blushed and blushed.

The rhythms in Kerouac’s bop prose, are not the rhythms of a car being yanked out of a ditch. The sounds are not close either. What a racket it must have been, and a sight and emotional sense for all to witness. But the pacing at first is as if Kerouac was somewhat out of breath, or maybe becomes a bit breathless as he recalls the event. In describing the beautiful daughter, we do not get her rhythms either, nor the rhythms of the wind blowing. We get the pacing of the witness (Jack Kerouac’s Sal Paradise), his vantage, his rhythms. We understand at once, how we could be him with his eyes, how this certain part of him seems to be a certain part of us, but in our own reflection, how we are different from him. Through his wording, we surmise as best we can, what was really taking place, both within the scene described, and within the describer.

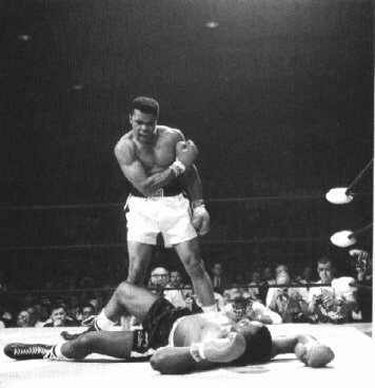

Imagine that Bernstein and Michaels could not make it to Las Vegas. Instead, the promoters asked if they could put a microphone up to Hagler in order that he give us, in his own words, the unfolding details of the fight. Could we expect poetry from his words?  I cannot help thinking of Muhammad Ali, who may have been poetic with his words before and after a fight, and maybe during as he taunted his opponents, but the poetry of his athletics was something else again. Bob Dylan is a poet in this wider sense, a song poet, which is different from being a word poet. Chopin is a poet of the piano specifically, and Marceau a poet of mime. The poetry of the artist or athlete is found in what is practiced.

I cannot help thinking of Muhammad Ali, who may have been poetic with his words before and after a fight, and maybe during as he taunted his opponents, but the poetry of his athletics was something else again. Bob Dylan is a poet in this wider sense, a song poet, which is different from being a word poet. Chopin is a poet of the piano specifically, and Marceau a poet of mime. The poetry of the artist or athlete is found in what is practiced.

Owen and Kerouac, were each able, at some juncture, to experience the poetry of the moments they relate–then as poets of the word, communicate such essence to us after the fact. In both cases, there is nothing goody-goody about what the people are doing. Owen’s war is evident. His hero is dying, a victim. Kerouac’s scene, on the other hand, involves the reckless destruction of a car, leading to the potential womanizing of a 16-year-old girl by a couple older guys passing through town. His heroes are culprits.

Whereas Owen has us look squarely at the dark side of human nature from the attitude of the light, Kerouac has us looking at the light from the vantage of the darkness. Hagler is doing the same as Kerouac, only instead of bringing fiction to an actual event, he actualizes a hoped-for event, walking through the necessary dark alley to get to the light–taking us with him like a good poet would. Here is such a poetic relationship with violence, through Iraq veteran and poet Brian Turner:

Turner begins his poem “Here, Bullet,” with what could have been the words of Marvelous Marvin Hagler if he could have scripted words into his fight with Thomas Hearns:

If a body is what you want,

then here is bone and gristle and flesh.

Here is the clavicle-snapped wish,

the aorta’s opened valves, the leap

thought makes at the synaptic gap.

Here is the adrenaline rush you crave,

that inexorable flight, that insane puncture

into heat and blood. And I dare you to finish

what you’ve started.

The world yearns for the good fight, a real live hero fighting for good to prevail, and knows the violence of it exists out there, even if in a far-off desert where poets or shamans sojourn, even if ducking from bullets in a tenement in New Jersey somewhere.

After the fight, Hagler spoke of his concern, that he hoped the fans got their money’s worth, the scheduled 15-rounder ending before the bell of the third round. He was assured that this was the case. This is not a necessary attribute of a poet, wanting others and posterity to benefit from individual inspiration. It’s good to see, though. But, whether they care or not, the poets’ service is invaluable, if only in that we come together as witnesses to each other and, therefore, ourselves. What’s even better, is if we can then continue with a conversation, informed by the poet. Here is the ending to Turner’s poem:

Because here, Bullet,

here is where I complete the word you bring

hissing through the air, here is where I moan

the barrel’s cold esophagus, triggering

my tongue’s explosives for the rifling I have

inside of me, each twist of the round

spun deeper, because here, Bullet,

here is where the world ends, every time.

As the modern poet, he accepts that he is shaman, who must complete the communicative process, and write it down for us, how “the world ends, every time.” He continues the conversation, from the vantage point of a soldier who has witnessed too often what Owen witnessed. It is from here, he seems to be responding to Carl Jung’s thoughts on death:

_____